the Louisiana Barrier Islands

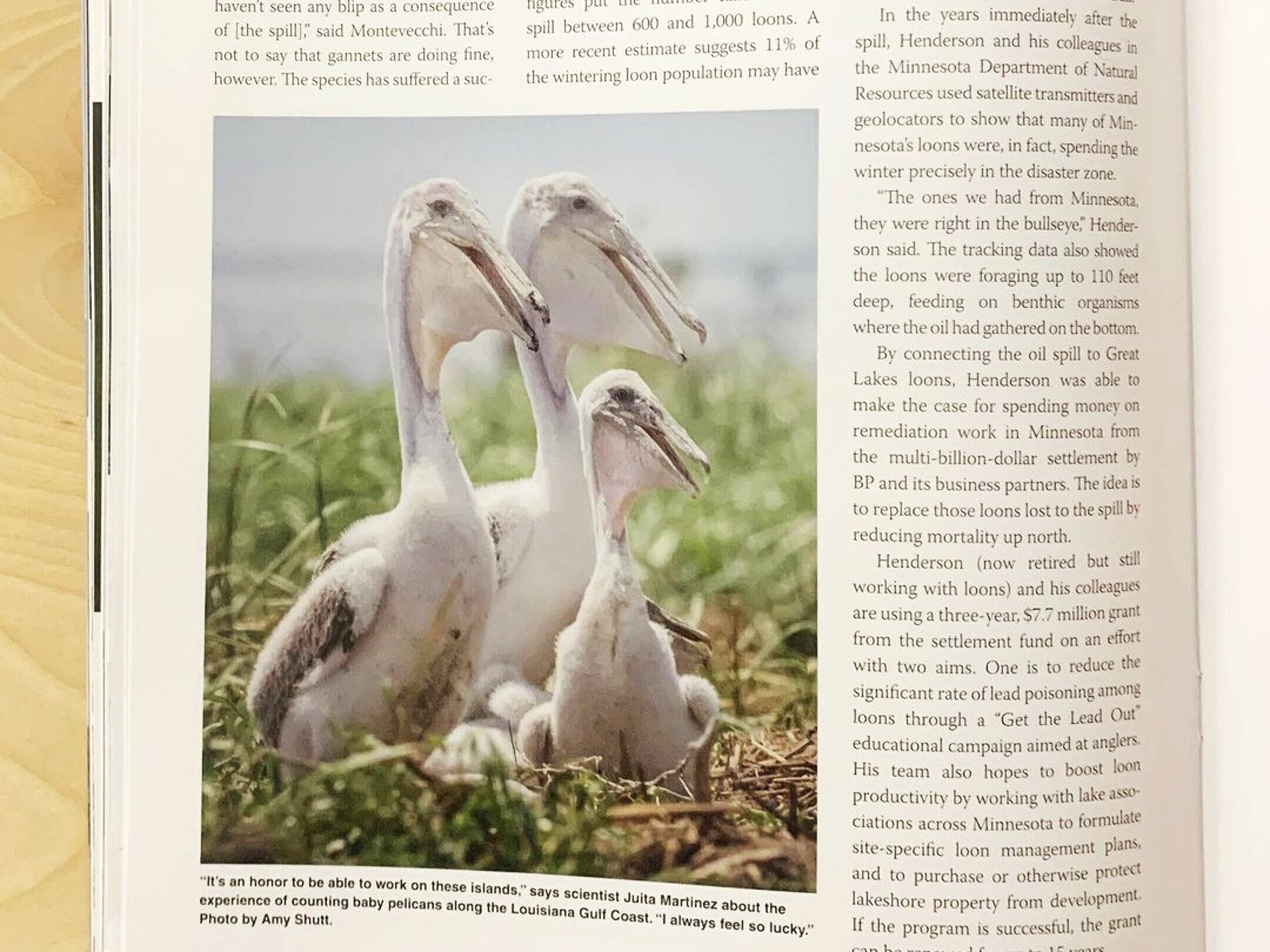

This collection of photographs focuses on the Louisiana barrier islands in the Gulf of Mexico. I was on assignment for Cornell’s Living Bird Magazine documenting the work of Juita Martinez, a PhD student at the University of Lafayette, which focuses on the seabird breeding colonies of these islands. Photographs accompany a print and online article for the Fall 2020 issue, written by Scott Weindensaul, which explores the area ten years after the BP Oil Spill of 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico.

The barrier islands of Louisiana are vital for the protection of Louisiana’s coastal communities and its natural resources. They are the first line of defense from summer’s hurricanes and winter’s storms; they mitigate ocean swells and other storm events for the water systems on the mainland side of the barrier island, as well as protecting the coastline. However, barrier islands are no longer building naturally.

Multiple wetland systems on the mainland such as lagoons, estuaries, and/or marshes can result from the above mentioned conditions depending on the surroundings. These areas are typically rich habitats for a variety of flora and fauna. Without barrier islands, these wetlands could not exist; they would be destroyed by daily ocean waves and tides as well as ocean storm events. One of the most prominent examples is the Louisiana Barrier Islands.

Also, without barrier islands, important nesting bird colonies would fail. Another primary goal of the restoration of Louisiana’s barrier islands is to protect critical nesting habitat of the Brown Pelican, especially on Raccoon and Queen Bess Islands, which hold very large colonies.

In the past 150 years, rapid erosion of the protecting barrier islands has exposed Louisiana's valuable wetlands and estuaries to increased storm waves and currents. (Modified from Penland and others, 1989.) Photo credit: USGS.gov

This area and its wildlife were hit hard during the Deep Water Horizon BP Oil Spill 10 years ago, which injured and killed some 100,000 birds of 102 species; about 6,165 sea turtles; as many as 25,900 marine mammals, and countless fish and other smaller marine animals of the gulf.

This group of islands, known as Isles Dernieres barrier island chain, is also experiencing some of the highest erosion rates of any coastal region in the world. Raccoon Island is experiencing shoreline retreat both gulfward and bayward, threatening the seabird nesting colonies.

The islands were not always a chain but rather one long barrier island. In the 19th century it had inhabitants and was a popular resort destination. The island was destroyed by the Last Island Hurricane of August 10, 1856, and “split” in half. Over 200 people perished in the storm, and the island was left void of vegetation. The highest points were under 5 ft of water.

As a result of the hurricane and subsequent tropical storms, Isle Dernière was fragmented into five small barrier islands we know today: Raccoon, Whiskey, Trinity, Wine and East Islands.

Note: Public access by any means to the exposed land areas, wetlands and interior waterways of these islands is prohibited without a permit.

RACCOON ISLAND and QUEEN BESS - RESTORED

Hover over images below to read the captions

Raccoon and Queen Bess are two of the islands that hold huge nesting colonies for seabirds, like the brown pelican, and both were greatly affected by the BP Oil Spill in 2010, in addition to the continued degradation brought on by constant wave action and rising sea levels. Raccoon Island alone has experienced a historic shoreline erosion rate of 27.9 ft a year between 1855 and 2005 and the area was decreased by approximately 300 acres from 1978 to 2005.

Raccoon Island, Louisiana's westernmost nesting site for colonial seabirds and wading birds is the state’s top nesting colony for the brown pelican, with Queen Bess being equally as important for brown pelican nesting colonies on Louisiana’s eastern coast.

Both Raccoon and Queen Bess are considered restored barrier islands and undergo continued restoration as need be to help rectify these effects and hinder future degradation. Constructing rock walls, called breakwaters, are one of the ongoing approaches used in restoration efforts.

In 2019, the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission approved a resolution that converted Queen Bess Island to a Louisiana state wildlife refuge to enhance protection of the island, a vital waterbird colony that annually produces more than 4,400 nests. It is the fourth largest brown pelican rookery in Louisiana, producing 15 to 20% of the state’s nesting activity. It also provides nesting habitat for about 10 species of nesting colonial waterbirds, such as tri-colored herons, great egrets, and royal terns.

In February 2020 a project was completed to restore Queen Bess Island’s available nesting habitat from 5 to 37 acres.

Philo-Brice and Felicity - Unrestored

Hover over images below for captions

Philo-Brice and Felicity are unrestored Louisiana barrier islands that also act as important nesting grounds for seabirds. Because they are unrestored they lack the breakwaters on the perimeter to protect them from the wave action and rising sea levels.

Subsidence is reducing both to their bare bones, which can be seen in the dark peat substrate underfoot. As the sea level continues to rise more and more of these islands will wash away, and eventually disappear.

Flip through the slideshow below to see more unrestored island photos and hover for captions

Research on the restored and unrestored barrier islands of Louisiana

Scroll through the slideshow below to see some of the views of a day in the life of biologist Juita Martinez as she works with her colleagues to collect data through leg banding and bird monitoring for her study researching the nesting colonies on restored and unrestored Louisiana barrier islands.

Hover over images below for captions